Because We Have Made God Too Small: A Baylor Professor’s Apology to Kaitlin Curtice

The chair scraped next to me. It was 2:30 on Friday afternoon—time for our scheduled break. For three years I have been writing every Friday afternoon with a group of faculty women, blocking our calendars and ignoring emails. For three years I break with them for 15 minutes, pulling our chairs into a small circle. For three years we have been working together, encouraging each other and motivating each other, as we all work toward full professor.

I confess I didn’t really want to stop for a break. Sand trickles all too fast from my hour glass. I am working to complete a book manuscript while continuing as a full-time academic dean. Fridays are precious to me. I don’t always feel I have time for 15 minute breaks.

So I wasn’t paying close attention to the conversation. I was thinking hard about my next paragraph—until I heard a familiar name.

“Wait,” I asked, “Kaitlin Curtice was at Baylor?”

What came next caught me completely off guard. Not only had I missed hearing Kaitlin Curtice speak during chapel, but a student had disrupted her talk, just like a student had disrupted Kathy Khang. And then I learned that the disruption had come when Kaitlin Curtice said, “the work of telling women that we do not matter as much as men do in society is dehumanizing. It is damaging to the soul..” The student reportedly shouted, “No one even thinks like that.” And then I learned that a student group posted a call for Baylor to formally and publicly apologize for bringing Kaitlin Curtice to the chapel service, calling her a “speaker with pagan sympathies.”

I sat in silence.

Shocked.

My computer screen stared back at me. Our 15 minutes was up. It was time to start writing again. But my focus was gone. Words ran through my head, too fast to pin down with keystrokes. Too jumbled to make sense. Too raw to show others.

Have we made God so small, I thought, that we cannot conceive of prayer language different from our 21st century words?

Kaitlin Curtice didn’t pray to “Mother Mystery,” as she was accused. But if she had, she would not be the first Christian to reference God as Mother—a historical reality I know all too well as a medievalist. Julian of Norwich, a devout anchoress who dedicated her life to prayer and devotion, did so in the fourteenth-century. “As truly as God is our Father,” Julian wrote, “so truly is God our Mother.” Just as Christians pray to God as Father, encouraged Julian, Christians should also pray to God as Mother. “Our Father wills, our Mother works, our good Lord the Holy Spirit confirms. And therefore it is our part to love our God in whom we have our being, reverently thanking and praising him for our creation, mightily praying to our Mother for mercy and pity, and to our Lord the Holy Spirit for help and grace. For in these three is all our life: nature, mercy, and grace…”

So – do we call Julian of Norwich, a medieval Benedictine nun who recognized salvation as coming through Christ alone, as having “pagan sympathies”?

Caroline Walker Bynum, in Jesus as Mother: Studies in the Spirituality of the High Middle Ages, argued that the “’mother Jesus’ of medieval religious writers” did not begin with either Julian of Norwich in the fourteenth-century nor even with women. A tradition of using maternal imagery for God existed among male monastics like Anselm of Canterbury and Bernard of Clairvaux since at least the eleventh century. “But you, Jesus, good lord, are you not also a mother?” asked Anselm in his prayer to St. Paul composed around 1070. “Are you not that mother who, like a hen, collects her chickens under her wings? Truly, master, you are a mother. For what others have conceived and given birth to, they have received from you. . . .You are the author, others are the ministers. It is then you, above all, Lord God, who are the mother.” By the way, Anselm drew his feminine imagery for Jesus directly from the New Testament (Matthew 23:37). Paul also inspired Anselm to use feminine imagery (1 Thessalonians 2:7 and Galatians 4:18-19).

So, again, are these devout male monastics “pagan”? Have we made God so small that there is no longer space in our American Christian world for these medieval brothers and sisters in Christ?

Or what about Hildegard of Bingen, a twelfth-century poet, author, musician, preacher, theologian, physician, and Benedictine nun who lived over 800 years ago in Germany? If we are concerned about Kaitlin Curtice’s nature references, what do we do with Hildegard’s explicit descriptions of mother earth? Listen to how Hildegard, so long ago, wrote a very Christian praise for mother earth.

The earth is at the same time

mother,

she is mother of all that is natural,

mother of all that is human.

She is the mother of all,

for contained in her are the seeds of all.

The earth of humankind

contains all moistness,

all verdancy,

all germinating power.

It is in so many ways

fruitful.

All creation comes from it.

Yet it forms not only the basic

raw material for humankind,

but also the substance

of the incarnation

of God’s son.

Will we call Hildegard of Bingen pagan? Will we question her Christianity, even though she wrote that “Believing persons should never cease to direct themselves and others to God”? Will we accuse her cry from more than 8 centuries ago, “The earth should not be injured. The earth should not be destroyed,” as political, leftist ideology? Or should we realize that Christians throughout history have called for humanity to take seriously our divine charge to care for the earth? As Hildegard pleaded, warned:

The high,

the low,

all of creation.

God gives humankind to use.

If this privilege is misused,

God’s Justice permits creation to

punish humanity.

Have we made God so small? That nature imagery and recognizing God as the life breath of creation sounds non-Christian to us?

Have we made God so small? That we reject feminism and racism as inappropriate topics for a university chapel forum?

The student in chapel allegedly shouted, “No one even thinks like that,” when Katilin Curtice mentioned the reality of Christian patriarchy. But Kaitlin Curtice is right. Throughout Christian history women have been considered less than men. Even the highly revered Augustine, Bishop of Hippo and author of the beloved Confessions and City of God, argued that women do not reflect, separate from men, the image of God. Building on Aristotelian philosophy that women were imperfect men, and fueled by the patriarchy of the Roman empire in which he lived, Augustine argued that women’s physical condition barred them from imago dei. “The woman together with the man is the image of God, so that the whole substance is one image. But when she is assigned as a helpmate, which pertains to her alone, she is not the image of God; however, in what pertains to man alone, he is the image of God just as fully and completely as he is joined with the woman into one.” He did concede it was possible for women to transcend their physical state, and reflect the image of God, but men always were imago dei.

And, for a modern example, John Piper’s evangelical empire is built on his belief that men are created to lead and women are created to follow. Piper does disagree with Augustine, arguing that women are too created in the image of God. But he also agrees with Augustine (and Aristotelian philosophy) that women are created to be subordinate to men. As he writes, “Paul would say a female is not a proper extension of male leadership…A woman teaching men with authority—week in and week out or every other week or regularly in an adult Sunday School class or whatever—a woman teaching men with authority under the elders is not under the authority of the New Testament. She may be under the authority of the elders, but she is not under the authority of the New Testament, and neither would they be for putting her in that situation.”

Oh, the student was wrong. Lots and lots of Christians, from the ancient world to our present world, believe that women are less than men (although I suspect modern folk will dislike my phrasing). Lots and lots of Christians also, often using the same verses that subordinate women, have supported slavery and racism

Just last July, Brantley W. Gasaway tweeted a long twitter response to Denny Burk. Burk had shared a criticism of women preaching in the early 20th century by Southern Baptist theologian A.T. Robertson. Burk called Robertson “one of the greatest scholars of New Testament Greek.” Gasaway countered that “Robertson was also a white supremacist.” Indeed, Gasaway recognized a continuity that historians have long understood—hierarchies of power that subordinate women walk closely beside narratives that support slavery and racism.

The New Testament household codes, for example, have long been used to enforce masculine authority over women as well as legitimize slavery in the American South. As Clarice J. Martin writes, “Authors of proslavery tracts appealed particularly to six New Testament texts to buttress their arguments: 1 Corinthians 7:20-21; Eph 6:5-9; Col 3:33, 4:1; 1 Tim 6:20-21; and Phlm 10-18. Stressing that since the biblical writers expected the dutiful obedience of slaves to masters, and that the slaveholders in the biblical texts were, after all, members of churches founded by Paul and other apostles, the defenders of human bondage contended that slaveholding was quite consistent with biblical teaching.” Christians who argue for biblical support of patriarchy must grapple with how these same texts have been used to support racism. Martin drives this point home for us in her groundbreaking article “The Haustafeln (Household Codes) in Afro-American Biblical Interpretation”: “How can black male preachers and theologians use a liberated hermeneutic while preaching and theologizing about slaves, but a literalist hermeneutic with reference to women?”

Racism and patriarchy have long been problems throughout Christian history, which makes them entirely appropriate for a chapel conversation.

Have we made God so small? That we refuse to recognize the dangerous realities of oppression that haunt our white Christian churches? That we refuse to even consider how we might be complicit in that oppression? (BTW have you read Jemar Tisby’s The Color of Compromise: The Truth About the American Church’s Complicity in Racism? It might change your perspective….)

But, at the end, I think what grieved me the most was the disrespect shown to Kaitlin Curtice by some of our students.

Have we made God so small that we cannot extend Christian hospitality to those who believe differently from us? Have we made God so small that we have become noisy gongs and clanging cymbals, forgetting that God calls us always to love?

I have been both a professor and a pastor’s wife for more than twenty years. I am solidly evangelical, solidly Baptist, solidly Nicene in my beliefs. Rather than be afraid of different perspectives and new ideas, rather than reject outright the different theology and practices of the people I study, I have learned that God can always handle my questions; I have learned that God’s love has always been big enough to include late medieval Christians as well as my Baptist faith.

Kaitlin Curtice, I apologize that you did not experience the love of Christ when you visited Baylor last week. I apologize that a small group of our students were so busy trying to discredit you, that they did not remember to listen to you. I thank you for having the courage to come, and I pray that our students will come to realize that the God we serve is bigger than they have imagined.

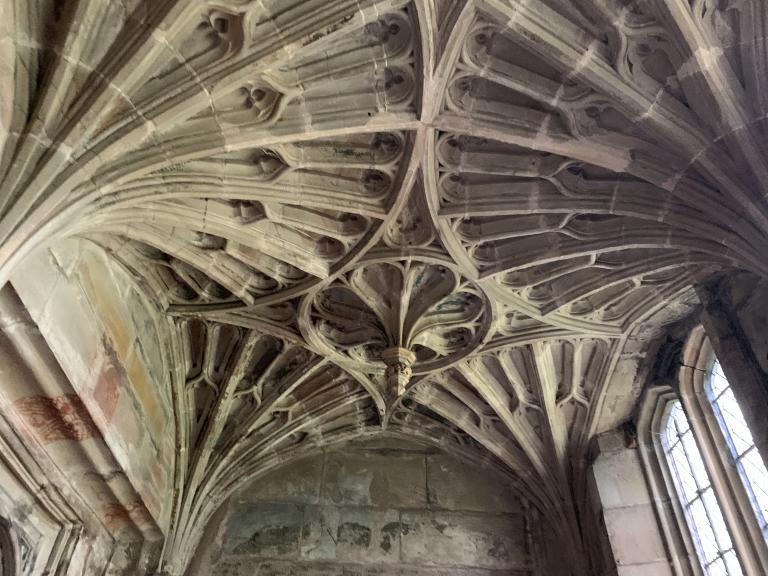

The images are from one of my favorite parish churches in Shropshire–St. Bartholomew’s, Tong. The substantial patronage of Lady Isabel, wearing the roses, built the present structure of the church in the fifteenth-century.

This is an outstanding article. I commend you for your argument. Any and every use of Scripture to defend actions, beliefs, or ideologies that are contrary to the love of God in Christ Jesus to all of humanity is a gross misrepresentation and misinterpretation of Scripture. This has been tolerated for far too long. It’s time for those who are ready to listen to hear.

I so appreciate the conversations you create between historical Christianity and today. Always insightful.