Jessica Hahn and Evangelical Silence on Sexual Abuse

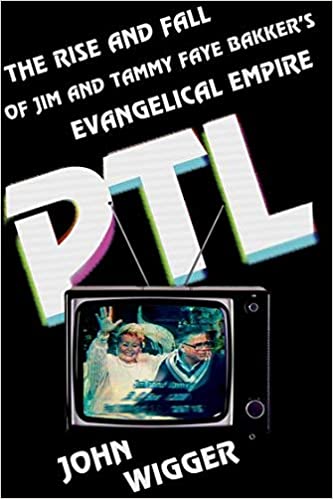

We are so pleased to welcome back John Wigger to the Anxious Bench. John Wigger is Professor of History at the University of Missouri and author of PTL: The Rise and Fall of the Evangelical Empire of Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker. #MeToo #ChurchToo

In 1980 Jessica Hahn was sexually assaulted by one of the most prominent preachers in America. Her experience reveals why our current dialogue about powerful men and the reluctance of survivors to come forward applies just as much to evangelicals as anyone else. For nearly seven years Hahn was pressured into silence. When her story became the center of a national scandal in 1987, she faced unrelenting scorn in the press and silence from the church. Thirty years later she has retreated into obscurity while her assailant, Jim Bakker, is still on television, preaching the gospel.

Evangelicals cannot afford to miss this moment of change. They need to take a long, hard look within. Jessica Hahn’s story is a good place to start.

For Hahn, the abuse began when she was in high school and attending a Pentecostal church on Long Island, pastored by Gene Profeta. The church was a refuge from her dysfunctional home and alcoholic stepfather. While she was still a teenager, Profeta, who was twenty-two years her senior, had a phone with a private line installed in her bedroom so that he could check up on her at night. If she got home late she knew there would be hell to pay the next day. “He would drag me by the hair into his office, throw me under his desk, and pull the earrings out of my ears,” Hahn says.

In December 1980 an aspiring television preacher and frequent guest speaker at Profeta’s church, John Wesley Fletcher, invited Hahn, then 21, to Florida to meet Bakker and babysit his children. What seemed the chance of a lifetime turned into anything but. Alone in the hotel room, Bakker, who was 40, forced her to have sex with him and “did everything a man could do to a woman,” says Hahn. After Bakker left, Fletcher returned to the room and brutally raped her, according to Hahn. Blood from her back, rubbed raw on the carpet, stained the sheets when she crawled back into bed.

Before the scandal broke, PTL had annual revenues of $129 million, 2500 employees, a 2300-acre theme park, Heritage USA, and a satellite network that carried Jim and Tammy’s flagship talk show five days a week. After Bakker abruptly resigned in March 1987, reporters and satellite trucks surrounded Hahn’s apartment, in West Babylon, Long Island. The media was brutal, at times referring to her as “the whore of West Babylon.” “I didn’t know how I was supposed to look, what I was supposed to say,” she later admitted, making it easy for reporters to mold her into a figure that would sell: the other woman who had shamelessly plied her charms on a powerful older man.

The coverage of Hahn’s story never really changed. As recently as 2011 she was challenged to explain her “affair” with Jim Bakker when she appeared on The View, hosted by Whoopi Goldberg, Barbara Walters, Joy Behar, Elizabeth Hassselbeck, and Sherri Shepherd. “What did you see in him?”, one of the show’s hosts asked her. “He’s not exactly hot.”

When I first became interested in Jessica’s story, it took months to find her. After letters on university stationery went unanswered, I flew to Los Angeles, rented a car, and drove to her house unannounced. As I pulled up her husband Frank was cleaning out their garage. He told me that Jessica had no interest in telling her story again. She had long since given up on anyone treating it with respect. Despite her misgivings, the three of us met the next day at a deli off Mulholland Drive, but it was only after my book on the rise and fall of PTL appeared that Jessica decided she could trust me. She still loses sleep over events stretching back more than forty years and the pain never really goes away. Today she lives on a farm and occasionally goes to church with her husband and friends. “By now, no one knows who I am,” she says. Church is only comfortable because few remember; silence the substitute for redemption.

Evangelicals have largely remained on the sidelines at this moment of cultural reckoning. They voted overwhelmingly for Trump despite his well-publicized views on women, and some defended Roy Moore in support of his fundamentalist posturing. Jim Bakker recently complained on his current television show about men being forced to step down after accusations of sexual misconduct without a trial, comparing it to lynching. “I don’t hug women anymore,” Bakker said, as if all of the fuss was about nothing more than that.

The gospel should challenge abuse of power, protect the vulnerable, and give voice to survivors. For evangelicals this is a conversation too long in coming, a silence that denies mercy and justice. In the past, evangelicals have been leading voices of reform, as in the formation of the abolitionist movement in the pre-Civil War north or the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s.

Where are those voices now?