The Death and Historical Afterlife of a World War II Soldier

Last Friday, 29 September 2017, we lost another World War II veteran.

Out of the more than 16 million men and women who served in the American armed forces during World War II, less than 600,000 survive in 2017. More than 300 die every day. As the Veterans Statistics page from The National WWII Museum in New Orleans reminds us: “Every day, memories of World War II–its sights and sounds, its terrors and triumphs–disappear. Yielding to the inalterable process of aging, the men and women who fought and won the great conflict are now in their late 80s and 90s. They are dying quickly.”

And with most of them, their stories will die too.

As a historian, I know how quickly memory fades. Within 1-2 generations after a death, even prized family stories retold every Thanksgiving at the dinner table and accompanied by pictures and laughter are forgotten. Indeed, my dabbling in Texas Baptist history has shown me how scarce sources are for ordinary people living in the early twentieth-century. Their historical footprints often span little more than scattered references in local newspapers and government records.

On the one hand, this doesn’t really bother me. As a Christian, I believe this life is fleeting. The afterlife that matters is the one to come, not our historical footprint. As a daughter, niece, granddaughter, sister, wife, and mother, small historical footprints also don’t worry me. A locket from my grandmother reminds me that the people we love shape who we become. My grandmother’s life may never appear in a historical biography, but that doesn’t lessen the significant role she played in forming the lives of her children and grandchildren. My daughter’s name echoes my grandmother’s name. She is remembered, even though my daughter never knew her.

On the other hand, as a historian, losing the stories of millions of everyday people terrifies me. Historians can only understand the past through the evidence that remains. The disappearing memories of WWII affect the story that future historians can tell.

Thanks to the Texas Liberators Oral History project, conducted by the Oral History Institute at Baylor University 2011-2013 and funded by the Texas Holocaust and Genocide Commission–more stories from WWII veterans have been preserved. The voices of 19 veterans collected from throughout the state of Texas help tell the story of the final weeks of World War II and the liberation of Nazi concentration camps.

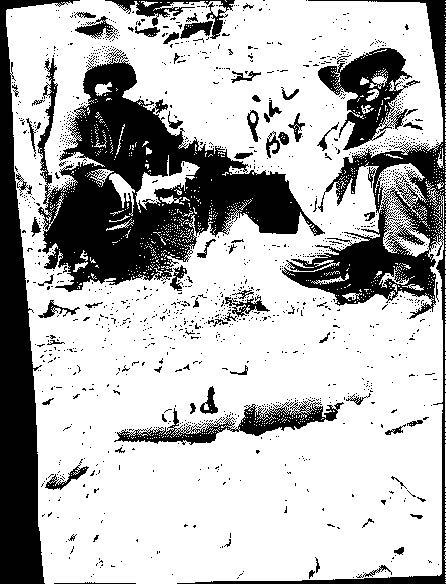

In April 1945, Raymond S. Watson—a young soldier from Ft. Worth, TX–served as a lieutenant in the Eighty-Seventh Chemical Mortar Battalion, Company C. “We shot smoke screens for when [the army] crossed–in river crossings and so forth, and then we shot the high explosives since it was 105–just about the same thing as a 105 millimeter.” One day he heard stories from an outfit serving near him about a camp with “a lot of dead people.” When he returned from the front line, the second day or third day after Buchenwald was discovered, he went to the concentration camp. Mostly he went because he couldn’t believe the stories he was hearing. “I didn’t believe it,” he said. “But I did after I got there.”

“[T]hey stacked the bodies. They were just stacking up. They’d have them facing one direction on the first layer. The next layer, they’d turn them around forty-five degrees, and then they’d go up about five stacks high. And they were–I couldn’t count how many people that were just–just dead. And every one of them were skin and bones. It was awful. I mean, the odor was bad and–well, you just didn’t think a human could treat humans like that….”

Even at the age of 89, when the interview was recorded, Raymond Watson hadn’t forgotten the sight of those stacked bodies. “I didn’t think how human being could treat other human beings that way. I really didn’t,” he repeated again in the interview. He also hadn’t forgotten the behavior of some of the American soldiers.

“The one thing I will say is, it did–we had some young people, and you know, some of them were–I don’t know. I guess they were hardened, but they would go–they see a ring or something on a dead body, they’d just cut the finger off and do that. I mean, some of that happened with our people. And that’s something I couldn’t take. I mean, anytime I found out about it, I tried to do something about it. But that trait, I guess, is in a lot of people, maybe all of us.”

When asked how the war affected him, the atrocities of the concentration camp or the horrors of the battlefield, Raymond Watson gave this answer. “If I needed to go back I was ready to go back in Korea…even though I had two daughters…But I felt that any situation like that, we need to do something. So I don’t know. It didn’t affect me to the point that I wouldn’t do it again.”

Raymond Watson was a man who saw the worst of humanity but was still willing to “do it again” if needed. His interview gives an eye-witness account of the liberation of Buchenwald. But it also broadens and deepens the historical narrative. It shows how a fourteen-year-old boy who accidentally burned down his family farm house (“so we moved into town,” he said) and chose chemical engineering at A&M University because he didn’t want to sit at a drafting board, found himself–barely 22 years old–walking through stacks of bodies in a Nazi concentration camp.

At 89 years old, reflecting back on his experiences, he made a striking observation about why atrocities like concentration camps exist–because ordinary people turn a blind eye. “I don’t know that just the basic people were much different than over here. I mean, a lot of them just didn’t pay any attention to really what was happening. And I think I see that over here from time to time. But I think they [the German people] got a real eye-opener.”

Raymond Watson never forgot the details of his military service. Thanks to the preservation work of oral historians, we will never forget it either.

In memory of my beloved grandfather, Raymond S. Watson, 1923-2017.