Wonder Woman and Complementarianism

It probably doesn’t surprise you that I have always loved Wonder Woman.

My mother will testify that it is one show my little sister and I refused to miss. It is also my first clear memory of watching TV.

The story of Wonder Woman, however, didn’t begin in 1975 with Lynda Carter as Diana Prince. It began with William Moulton Marston, the 1941 creator of the Wonder Woman comic book character. Marston, as many articles have recently noted, had a clear vision for his female heroine: “to set up a standard among children and young people of strong, free, courageous womanhood; to combat the idea that women are inferior to men, and to inspire girls to self-confidence and achievement in athletics, occupations and professions monopolized by men.” Want to go buy your daughter a Wonder Woman action figure and t-shirt now?

Of course, Marston had some serious quirks (including living with both his mistress and his wife in a weird threesome). So don’t get me wrong. I am not certainly not idolizing Marston. But he did spin us a fascinating story. A story about women so strong and powerful that they move faster than the weapons of men; a story where women lead in the highest levels of society; a story in which the bonds of patriarchy really can be broken. A story in which gender equality really is possible.

Paradise?

It certainly seemed paradise to Marston, as he called Diana’s home Paradise Island. It also seemed paradise to the feminist utopian fiction from which Jill Lepore, The Secret History of Wonder Woman, states that Marston drew his Wonder Woman story. It is interesting to me that Marston’s original vision of a utopian world, in which women exist in a single-sex society free from male oppression and even male influence, is changed in the new movie. Diana, instead of being the product of prayers by her mother, is now the product of a traditional male/female relationship. Instead of Diana being powerful because of her female heritage, she is now powerful because of her father. A rather significant change that (after doing some research) I learned stemmed from a relaunch of Wonder Woman in 2011. A recent Vox article calls this the “Zeus-you-are-the-father” reveal and points out that it “fundamentally redefines Wonder Woman.” Wonder Woman (according to the 2011 comic story) now is a product of a traditional patriarchal relationship, her female society does have significant interaction with men (they reproduce by kidnapping and raping sailors), and Wonder Woman herself learns about her history and her powers (indeed, she discovers the full force of her powers) from the teachings of a man (actually male god).

Regardless of whether you prefer the origin story of the Lynda Carter Diana Prince or the new more complex Gal Gadot Diana, Wonder Woman’s roots are much deeper than even Marston and early twentieth-century fiction. Diana was born, of course, in the story of the Amazons.

I teach about the Amazons regularly in the first part of my Women in Europe class. My power point includes a picture of Wonder Woman and a link to her origin story (her first origin story). Students love this day. We talk about Homer and Herodotus and Plutarch. They describe female warriors who wear trousers, fight and kill male warriors like equals, and who live in a female-only society dedicated to military exploits. This is the world of the Amazon queens Hippolyta, who lost her girdle to Hercules, and Penthesilea, who was killed by Achilles in hand-to-hand combat. Herodotus tells us that the “womanly arts” of the Amazons were “to draw the bow, to hurl the javelin, to bestride the horse.” We also talk about those graves in ancient Scythia where female skeletons are buried with weapons and show evidence of battle wounds. We read Sarah Pomeroy, who explains how “Matriarchal societies–in the sense of totally female, rather than female-dominated, societies–are described in Greek literature and art for all periods.”

And we discuss the historical reality of the Amazons. Did Amazons really exist? Or were they just a myth? The jury is still out on this one, although most scholars think the legend of the Amazons was always bigger than their reality. Sarah Pomeroy suggests that “the fact that may Greek heroes had to test their strength against them leads one to suspect that the Amazons could have been either a totally mythical fiction or a group whose eccentricities inspired many false tales.” Likewise, Kim Phillips in her more recent article “Warriors, Amazons, and Isles of Women,” suggests that Amazon stories persist not because they were necessarily true but because European male audiences “liked the image of a woman with a sword or a bow or living without male governance so long as she was far from from them.”

In other words, the story of Wonder Woman, like the story of Amazons, persists and entertains because–even though we can imagine Paradise island–none of us really believe it is real. It is too extreme–not only are women as powerful as men and rule like men, but they live without the need (possibly even the desire) of men.

Less than 20 years after Lynda Carter fought her way on screen as Wonder Woman, a book was published which taught something both very different in content from Diana Prince yet similar in its level of extreme. It was John Piper and Wayne Grudem’s Recovering Biblical Manhood and Womanhood: A Response to Evangelical Feminism, published in 1991. It argued (as John Piper has so recently stated) that male headship and female submission “are integral with nature and grace, creation and salvation.” Women, according to Piper and Grudem, were subordinate to men from the very moment of creation and will continue to be subordinate even into eternity. A 2006 article in the journal for the Council for Biblical Manhood and Womanhood, built on the foundation of the 1991 book (and the 1988 Danvers Statement), argues that, “There is every reason to believe that gender-based distinction of roles will remain [in the new creation]. The social fabric of gender-based distinctions of roles was weaved in a pattern that accords with the prelapsarian decree of the Creator.” Women were, and will eternally be, subordinate. In this world, the Amazons and Wonder Woman became even more mythological because they could never exist. Woman as subordinate to man and dependent on man is woven into the fabric of creation.

I found myself thinking about complementarianism while watching the new Wonder Woman movie. One of my favorite scenes in the movie occurs in the London department store Selfridges (if you are ever in London, go check out the food hall!). I can’t help but wonder if Diana’s attempts to find a more era-appropriate outfit reflect one of Marston’s original Wonder Woman themes–breaking the bonds of patriarchy. Instead of being tied and shackled by bad guys, like the comic-book Diana, the 2017 Diana finds herself restrained by skirts and corsets of WWI-era female fashion. Neither Diana is held for long by the bonds, but I particularly like how the Gal Gadot Diana kicks out her skirt.

And this is what made me think of complementarianism. Wonder Woman, and probably the Amazons too, is a story. Yet it also represents an idea, a very enduring idea, that something is wrong with a world that oppresses and limits women. Maybe women can do more than the “womanly arts” of domestic life, as the Amazons in Herodotus claimed. Maybe women and men are called to something greater than culturally-defined gender roles (again the image of Gal Gadot kicking our her skirts in Selfridge’s comes to mind). As Scott McKnight has written, “Jesus ignored what tax collectors, zealots, prostitutes, Samaritans, centurions, the rich, the poor, men, and women were ‘supposed’ to be. Instead he invited them to something greater.” Just as Mary sat at the feet of Jesus to learn instead of cooking with Martha, maybe women (like Diana Prince?) can do what God has called them to do instead of what culture has prescribed.

But complementarianism seems to remove this possibility.

Of course, the idea that women were created subordinate to men wasn’t invented in 1991 (nor even 1988 for that matter). It has a long history, including such revered thinkers as Aristotle (who argued that women were deformed men) and even the church father Augustine. Yet, a long history of similar arguments (I have to add arguments mostly by men…) doesn’t negate the fact that the complementarian movement is a very recent development. It was born precisely to combat growing support of egalitarian theology and fears about feminism. Just listen to the words of Wayne Grudem: “it seemed to me that the church was being led astray by misleading and false information, and incorrect biblical arguments, that were being put forth by evangelical feminists…several of us at [the meeting of the Evangelical Theological Society in Atlanta in 1986] believed that the lineup of speakers did not at all represent the viewpoints of the vast majority of members of the Evangelical Theological Society. We had a series of meetings in private that led to the writing of the Danvers Statement in 1987, and the public announcement of the formation of the Council on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood.”

Now, as a Christian, I am troubled by the myth of Wonder Woman. Did God create women to exist and flourish apart from men? No. Regardless of what you think about gender hierarchies, God clearly created men and women to work together. But I am also troubled by complementarianism. Did God create a hierarchy where women are eternally, both pre and post the Fall, subordinate to men? Does this really fit with the character of God? Is this really good for men, much less for women? Do the words of Jesus which fight against hierarchy, calling for the first to be last and the last to be first, and the words of Paul that there is neither male nor female in Jesus Christ really not apply to relationships between men and women? Is feminism really “a rebellion against God’s created order”?

Or is there another option. Is perhaps complementarianism not as timeless a concept as claimed? Rather than being eternal, could it have been created (as so many other ideas have been) in a specific historical context by people influenced at least as much by contemporary culture as they were by the Bible?

Everything really does have a history.

Sometimes, when we explore that history, we find the historical reality is more complex than we realized. Sometimes, as with the Amazons, we simply find more myth than reality. At the very least, perhaps before accepting the eternal reality of complementarianism, we should pay more attention to its historical construction. We might like to think that theology (at least our theological understanding) isn’t influenced by contemporary culture, but history teaches us that it usually is.

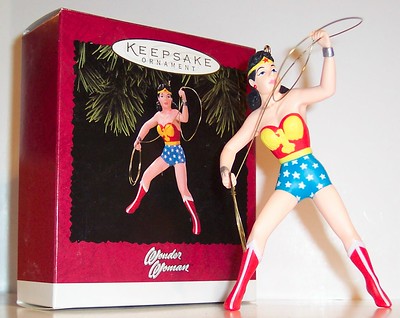

(This post is for my sisters and my mom–real life wonder women who love Jesus too. And I used the image of the Hallmark ornament because I have owned this ornament for over 20 years.)